In May, 2008, our cousin Hans Georg Hoffmann dedicated a "stumbling block" in a street in Berlin-Mahlsdorf in honor of Walter Reissner (1879-1943).

Contents

- Background Notes by Dorette R. Schaefer

- Address on the Embedding of a Stumbling Block

for Walter Reissner (1879-1943) by Hans Georg Hoffmann - Comments by Hans Georg Hoffmann

- Excerpt from Master's Thesis of Margaret Ewing

- Obermayer German Jewish History Award - Gunter Demnig

Background Notes by Dorette R. Schaefer

It all began with a hint from Gubener Andreas Peter last January, to google for sculptor and painter Walter Reissner, brother of my grandfather William. To my surprise there was a lot of information on him based on several sources, of which I had no idea that they existed. Some of the information was wrong, i.e., they claimed that his brother Hans was his father, etc.

When trying to contact the writers for this particular google bit, I got a very nice reply from Berlin high school student Anika Taschke, saying that she and some of her class mates were researching erstwhile Jewish residents in their neighborhood. They found the family Lange and Walter Reissner, and they were engaging their efforts to have Stumbling Blocks embedded in front of their former homes. Stumbling Blocks were created by artist Gunter Demnig as a form of remembrance; see below.

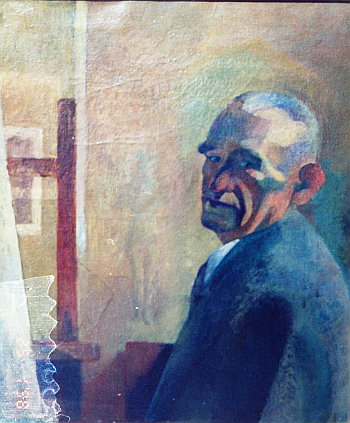

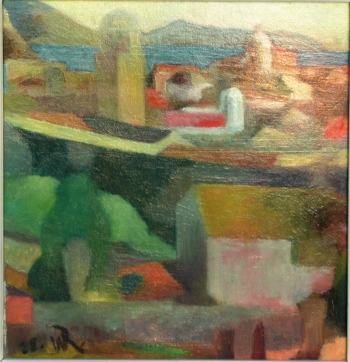

Anika was pleasantly surprised to find distant relatives of WR, who were able to give her some more information and, above all, copies of two of his paintings, his self-portrait and a landscape, showing Dubrovnic dated 1928. They seem to be the only items left from his work.

The ceremony was planned toward the end of May, and when I realized that I was not able to accept the invitation to participate, I thought of Hans Georg, recalling that he was living in Berlin. Was he ever surprised to learn about what was going on in his extended neighborhood (as it turned out) from someone living in the U.S.! He did some more research, was able to participate in the ceremony, and he gave an excellent speech as you can see below.

|

|

Self-portrait by Walter Reissner

|

|

|

Ragusa (Dubrovnic) by Walter Reissner

|

Address on the Embedding of a Stumbling Block for Walter Reissner (1879-1943), May 22, 2008, in Berlin-Mahlsdorf

by Hans Georg Hoffmann

(translated by Dorette R. Schaefer)

It was end-February in 1943, and Berlin still was not yet "cleansed of Jews". In a gigantic operation, Jews were now captured at forced labor sites in factories, in apartment buildings, on the street, wherever they were found.

A police car stopped in front of the one-family house at Eichenhofweg 9 around noon early in March. "Come along! Hurry up! Faster!" Was he prepared, had he packed a suitcase? Or did the 64-year-old Walter Reissner, widowed for 10 years, live in the belief that he somehow would be excluded from the deportation fate of Berlin's Jews? Weren't his participation in World War One and the subsequent loss of a leg enough proof for the fact that he was "a good German?"

After several more Jews were picked up, the truck then drove them to the former Jewish old people's home on Grosse Hamburger Street, where they were distributed onto different transport trains. Chaos and despair were in the air. Many had been caught without their closest relatives -- mothers without their children, children without their parents. Many sensed that this would be a journey without return. In March 1943, people who still didn't know what was happening to Jews didn't want to know. The 85-year-old widow of the great artist Max Liebermann knew it for certain; she took poison when SS-men came for her.

The Berlin journalist Ruth Andreas-Friedrich wrote in her diary Sunday, February 28, 1943: "Since this morning as of 6 AM, trucks drive through Berlin guarded by armed SS-men. They stop in front of factory gates, in front of private homes. They are loading up human freight. Men, children, women. Under the grey covers, disconcerted faces. Distressed figures, people reduced to misery, are penned up like cattle and drawn apart. More and more are pushed onto the crowded trucks beaten with clubs. Within six weeks, Germany is supposed to be "cleansed of Jews".

During the night of March 1-2, 1943, Berlin experienced its most horrible bomb attack yet. Entire blocks of houses were bombed to rubble and ashes. Bombs had also fallen around the Grosse Hamburger Street. Walter Reissner was put on the "34th Transport East". The train left the Berlin Grunewald freight station on March 4, 1943, with 1128 people and arrived in concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau on March 6.

Let us not try to imagine the misery of this endless journey. The people, who after more than 30 hours arrived on the ramp in Auschwitz, were unbearably thirsty, weak, dirty and in despair. Some were too weak to leave the train on their own. They were pulled outside, thrown onto trucks and shot next to the crematoriums. The others were "selected". 389 men and 96 women were directed to the right in rows of five, which meant they were selected to be slave laborers at the camp; the rest of the 643 people were directed to the left: mothers with children, the old, the weak -- for them the gas chamber was waiting.

For a last time these doomed people were given a hint of hope when they were guided into the "Shower and Disinfection Chamber". There were numbered hooks, and they were instructed to remember their numbers so that they would find their belongings afterwards; shoes had to be tied together.

The hundreds of people were ordered to take off all their clothes, and when the women and men -- old and young and children -- hesitated in shock, the voices of the SS-men became impatient and threatening. Walter Reissner had to part with his wooden leg. This wretched group of naked people had to move toward the next chamber. When all were standing closely packed inside, the door was locked. Outside a Red-Cross car stopped, an SS-officer got out carrying a metal jar. Helpers lifted the heavy lid of the roof of the gas chamber; the SS-man broke the patented lock of the metal jar and poured the contents into the opening: the poison Cyclon B.

Not until ten minutes later had the last screams from the gas chamber stopped. The door was opened and the dead bodies, entangled into each other, were examined for hidden valuables by Jewish inmates of a special squad; after they had removed gold teeth and women's hairs the corpses were thrown into the crematoriums.

About 1.5 million people were murdered this way in Auschwitz. The 64-year old sculptor and painter Walter Reissner was one of them. He was a cousin of my maternal grandfather Dr. Carl Goldberg. In other words, the father of Walter Reissner and the mother of my grandfather were siblings. What I find particularly moving: The grave site of the common grandparents of Walter Reissner and Carl Goldberg, which is also the grave site of my great-great-grandparents, is fully intact to this day in the Jewish cemetery in Guben, kindly guarded by the Protestant minister who lives on the cemetery.

However, the family relationship is not important in this case. Instead we must try to comprehend the many millions of victims of Germany's darkest era as relatives of all of us, and within our limited possibilities we must embrace them in our memory. This happens in history books, at memorial sites as well as in the form of memorial stones, like the ones we embed today for Walter Reissner and the Lange family. With this gesture we do something for the memory of these poor people; but we also do something for ourselves, for our heart, our soul, our conscience, our culture.

When I was recently re-reading the horrible eye-witness reports on concentration camp Auschwitz, I suddenly felt a longing for something beautiful and noble to read, to watch or to listen to: a poem by Goethe or Heine, a passage from Fontane's "Stechlin", music by Bach, Beethoven or Brahms. But I was aware of this: I can't have the one without the other -- Goethe as well as Auschwitz are part of German history, German culture! And true also is a remark by Germany's former president Richard von Weizsaecker which I saw last week on a memorial for the Jews of the city of Wolfenbuettel: "Those who close their eyes to the past will be blind to the present." And impressed on my mind is also what another former German president, Gustav Heinemann, said: "There are difficult fatherlands. One of them is Germany. But it is our fatherland."

I thank Anika Taschke and her classmates for doing something for the dead and for us: for the dead, by pulling them from anonymity and enforcing remembrance; for us by stimulating us to pause, to think, to remember, to feel compassion, and to be thankful that today we live in a peaceful, democratic country in which the state can no longer deprive any of its citizens of their rights, nor rob, torture or murder them.

Comments by Hans Georg Hoffmann

"The ceremony itself was natural, dignified, and pleasant. This is not a given with such events. The deputy mayor, for example, delivered a sensitive, intelligent address: firstly about the people who were deported from here to be murdered (besides Walter Reissner the memorial service was also meant for a family of six, incl. two babies); secondly about the "culture" of remembrance especially in our district of the city, where many streets and institutions are named after Jews; and thirdly about neo-Nazis, who still have to be dealt with.

Then the artist Gunter Demnig spoke. He has embedded thousands of these truly beautiful brass-plated cobblestones in Germany and Austria. He is a sensible, intelligent person. And finally Berlin high school student Anika Taschke did her very best. She is a fine girl, a true pleasure to meet. The ceremony took place in front of the former property of the Lange family (six stumbling blocks); from there we drove on to Walter Reissner's former house, in front of which his stumbling block was embedded."

|

|

|

Gunter Demnig

|

Hans Georg Hoffmann,

Walter Reissner self-portrait, and Anika Taschke |

Excerpt from Master's Thesis of Margaret Ewing

[From "Re(-)presenting History: Installation Art in the New Berlin", Master's Thesis, School of Art+Design, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, October, 2007.]

Gunter Demnig's Stolpersteine, small gold bricks laid into Berlin sidewalks, are so seamlessly integrated into their environment that it often takes an introduction to see them for the first time. Though people walk over them every day, most people don't pay close enough attention to their surroundings to notice. On a walking tour of "Jewish Berlin" in 2005, my guide stopped short on a street corner and pointed to the sidewalk. Though I had been down this street before, I had never noticed the set of engraved bricks there. The Stolpersteine are four inches square, each giving the name and birth year of someone forcibly removed from the site, the date of deportation and concentration camp, and the date of death (murder) when known. Often, the bricks are arranged in family groups, and it is chilling to contemplate the everyday domestic lives that were violently interrupted... The stones for children are particularly unsettling. Each inscription begins, "Hier wohnte" ("here lived"), marking these sites as the victims' homes. These "stumbling blocks," as their name translates, have a double reference; they are literally stones built into the often uneven sidewalks and at the same time disruptions into our perception of the city; they insert this history of trauma into its public spaces, making it difficult to ignore or forget once you become aware of the bricks.

Once introduced to this project, I began to see the bricks everywhere, on streets I had walked down many times, even in front of a friend's apartment building. Now aware of this network of memorial stones, my perception of the city had shifted, and a heightened awareness of history began to color my daily activities. Not contained in a museum, nor even in a single site, the Stolpersteine pervade the whole city, integrating history into the spaces of everyday life...

(Margaret Ewing is a great grandniece of Walter Reissner.)

Obermayer German Jewish History Award

Gunter Demnig of Cologne, Nordrhine-Westfalia received an Obermayer award in 2005 for the Stolpersteine project. The award document is available as a PDF file.